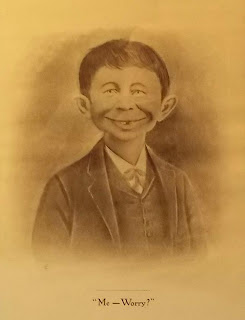

What? Me Worry? Isch ka Bibble and Alfred E. Neuman

In an earlier post, I point out that the Alfred E. Neuman

face and catch phrase originated from the advertising poster for The New Boy, a

stage play that was first performed in 1894.

The changes in the wording of the original phrase from “What’s the good

of anything? – Nothing!” to “Me-worry?” and “What – me worry?” may have been

further influenced by the “I should worry" craze of the early 1910s.

Isch ka Bibble:

I never care or worry

I never care or worryIsch Gabibble - Isch Gabibble

I never tear or hurry

Isch Gabibble - Isch Gabibble

. . . .

I should worry if

they steal my wife

And let a pimple grow on my young life

Isch Gabibble - I should worry?

No! Not me!

And let a pimple grow on my young life

Isch Gabibble - I should worry?

No! Not me!

So say the lyrics to a hit song from 1913, Isch Ga-Bibble (spelling from the

published sheet music; Isch ka Bibble

as spelled on the record label of the recording by Ed Morton), words by Sam M.

Lewis, music by George W. Meyer. The song introduced the faux Yiddish

gibberish word, ‘Isch ka Bibble,’ in all of its variant spellings, into the

public lexicon. The phrase would reappear in the 1930s as the name of a comic

character on Kay Kyser’s Kollege of Musical Knowledge radio program. Isch ka Bibble’s English language ‘translation,’

“I should worry,” entered the popular lexicon in an even bigger way.

The Washington Herald (March 26, 1914), published a story

about an investigation into Isch ga bibble by the Washington DC correspondent

to the Cologne (Germany) Times:

“Isih ga bibble?" “Whaddyemean.

'Isch ga bibble?’” asked the Germans who live in Germany when American

tourists "pulled" the phrase during their wanderings in the

fatherland.

"It's German," responded

the tourists. "Don't you know your

own language?" Now, Germans, as

everyone knows, are a serious-minded people.

So they began to think that maybe they didn't know German after all, and

grew worried about it. As the tourists

journeyed the phrase spread, and pretty soon the whole empire was wondering

about "Isch ga bibble."

Finally, a German newspaper decided

to settle the question, once and for all.

So the other day Dr. George Barthelme, Washington correspondent of the

Cologne Gazette, received a terse message from the home office, something to

this effect: "Probe Isch ga bibble. Americans here call it German. Rush details."

“I should worry,” remarked Dr.

Barthelme, reading the message. Thereupon

he got busy. Success crowned his efforts. Last night he sent a story back home telling all about it. Here is what he found out:

he got busy. Success crowned his efforts. Last night he sent a story back home telling all about it. Here is what he found out:

There is a saying common among

German Hebrews meaning about the same thing as "I should worry " The

saying is: "Nlsch gefiddellt." In a Hebrew theater In New York one of

the comedians "put across" the line.

An American song writer in the audience heard it, didn't understand the

correct pronunciation, and wrote It down the way it sounded to him.

"That's the way it ought to be. anyhow." he remarked. So he wrote an

"Isch ga bibble" song and It went all over the country, and everybody

shrugged their shoulders and said "Isch ga bibble," and It got back

to Germany that way.

And now that Dr. Barthelme has

found out what it's all about the German mind will be relieved and everybody

will be happy, and will say- "Just like Americans, nisch gefiddellt",

and the Americans will keep right on saying "Isch ga bibble."

Whether a ‘mistake’ or intentional, the word stuck and helped elevate “I should worry” into a national craze.

I Should Worry:

“I should worry” seems to have been an example of what we would

now call a meme. It was considered a

dismissive, sarcastic, snarky remark, along the lines (as best as I can tell)

of today’s “yeah, whatever” or “I could care less.” Although the "I should worry" fad seems to pre-date the song, the song lyrics illustrate how the phrase was used and may have helped propel the craze even further.

The following cartoon from The San Francisco Call (August

10, 1913) also illustrates how the phrase was used and how it was viewed by more conservative members of the older generation:

Then, as now, there were fuddy-duddies who resisted

pop-culture. The Day Book (January 17,

1914) reported that “Mrs. W. J. Zeh, president of the Perboyre Art and Culture

club, wants to abolish the phrase, ‘I Should Worry.’” She was looking for young people to suggest suitable

replacements for the phrase. The

reporter, on the other hand, suggested leaving the phrase alone to die a natural death like the earlier fads, “Oh, You

Kid” and “For the Love of Mike.”

A travel writer reported that:

London’s hotels and lodging-houses

are filled to the skylights with blooming Yankee tourists. Never before has the city welcomed more

travelers who say, “I should worry” and gnaw pepsin gum and demand the baseball

scores by cable.

The Day Book (July 26, 1913).

But not everyone was so negative. Glinda, the

Good Witch of the North, for example, approved. Billie

Burke, who later played Glinda in the 1939 movie, The Wizard of Oz, was quoted as saying:

But not everyone was so negative. Glinda, the

Good Witch of the North, for example, approved. Billie

Burke, who later played Glinda in the 1939 movie, The Wizard of Oz, was quoted as saying:

I think the man who invented the

slang phrase, “I should worry,” almost deserves a Nobel prize.

The mere fact that almost

everybody in the United States is saying this little derisive sentence over and

over to themselves daily is a sure sign that a great many of them will begin to

understand that worry is the most foolish of all the unnecessary things with

which women torture themselves.

The Day Book (May 20, 1913).

Dr. L. K. Hirshberg of Johns Hopkins University agreed with the Good

Witch; he prescribed repeating “I should worry” fifty times daily, loudly and

with conviction (increase dose as needed), as a cure for chronic worry. The Salt Lake Tribune (May 11, 1913).

The “I should worry” meme was repeated in many different variations:

She Should Worry - The San Francisco Call (August

10, 1913)

We Should Worry – Tacoma Times (October 21, 1912)

They Should Worry – The Day Book (April 5, 1913)

and, Me – worry? – Harry S. Stuff (1914)

Harry Stuff filed for copyright protection for his "Eternal Optimist" or "Me - Worry?" image in 1914, at the height of the "I should worry" craze. Although the image was likely based on or inspired by the earlier poster for The New Boy (as discussed in my earlier post), the rewording of the phrase to "Me-Worry?" (or "What? - Me Worry" as it appeared in later iterations of the image) seems to have been influenced by or was part of the "I should worry" craze of the early 1910s.

Harry Stuff’s image was

the subject of a law suit in the 1960s.

Harry Stuff’s widow sued Mad Magazine for copyright infringement. Mad Magazine prevailed.

(Watch a two-minute (or less) summary of the History of Alfred E. Neuman - click here.)

Fascinating. I've been researching the 1913s & 1914s and have found a lot of "Isch ga bibble" references. Your blog posts intrigue me!

ReplyDeleteGreat work with a now somewhat obscure reference, but one my parents used frequently...takes me back - thanks!

ReplyDeleteWhen I was a kid I saw an old slot machine at an antique place with Alfred E Neuman faces as we'll as fruit and jackpot logos. It was way older than Mad magazine or comic.That kid was a relic of old days. They used to use him on advertisings in the Victorian age. I love what Mad did with the character over the years but it kind of bothers me that they could copyright it. I mean it bothers me a very small amount.

ReplyDeleteThank you very much for posting this, with all the detailed examples. I was trying to find out what why a dancing party in 1913 had the theme of "We Should Worry". Makes sense now.

ReplyDelete